Salt Tea

PART I

Mrs Van Dijk looked into the deep water from the wood jetty seeing first her reflection in the water like a ghost and then beyond, the silvery flash of big fish. Sometimes the water swirled with dark plumes of dirt or slime, but sometimes it was clear. The noise from the small harbour was clamorous – women were selling fish, fishermen shouted at each other across the water between the moored boats. Dogs barked.

She had come to the jetty to get away from the people and the noise. She looked back at the quayside trying to see Howard. She’d been waiting an hour. Fishermen in a boat just coming in across the placid water came close to the jetty and noticed her and shouted. She wasn’t sure what they said because the accent was so strong but there was a masculine jeer in the sound of their rough voices. She was glad she couldn’t understand.

She kept her eyes low, not wanting to encourage any more shouting and held the straps of their two large bags in her hand tightly. She looked again down the jetty for a glimpse of Howard.

She wished he’d said where he was going, and how long he would be. It was already late in the day and they’d have to get a boat this evening or they would have to stay somewhere in Boston. It didn’t seem a nice place. The place was hardly a port at all. There were buildings behind the simple quayside – some tall – and the famous tall church tower called the Boston Stump, but the port buildings were poor and low. The water was muddy and smelly. It was more like a place that had been hollowed out from a marsh or a swamp than a proper port.

She began to regret coming. To remind herself of the reasons for setting out, she opened her bag again, looking for the letter. She’d read it three times already since leaving the Vale early in the morning. She took it out again.

Dear Mrs Van Dijk,

Thank you for sending your manuscript on the ‘Flowering plants of northern Europe’, which we received in good order. Myself and another editor read the text with great satisfaction and even happiness.

I don’t mind telling you, Mrs Van Dijk, that we were very concerned on hearing of the death of Dr Wroclaw so far from home, in England, especially since we received from him only a few days before a letter in which he discussed entrusting you with the completion of his great work.

I’m glad to say that the work has been done by you to a superb level of detail and requires only the minimum of editorial alteration. To continue our discussions we would very much like to invite you and your husband to Amsterdam, Netherlands. We will of course reimburse the costs of your journey and will pay you your fee for the completion of the work.

Please write by return of post to confirm when you intend to travel. Our address is at the top of this letter.

Underneath was a complicated and elaborate signature with many curls and flourishes. No name appeared, only the name of the publisher in large letters at the top.

She had written a reply immediately after receiving the letter saying that she and Howard would come that same week. This is why she now waited on the jetty smelling the fishy air and the mud of the channel that led to the open sea. Howard had gone looking for a boat that would take them to the Hook of Holland leaving that afternoon.

She put the letter back in the envelope and then the envelope into her big bag. Looking up she saw Howard striding down the jetty toward her. He always walked quickly and when he walked she always found it difficult to tell his mood. He had a small bag over his shoulder and his hair was longer than usual, his face was sunburned red.

But his face wasn’t optimistic. She could tell he hadn’t found a boat. Her sprits fell. She let go the straps of the two bags and sighed heavily.

She turned back to the sea. Perhaps because she didn’t want him to see her disappointment.

‘I couldn’t find anything. There are boats going to Holland but none to the Hook. They won’t take passengers anyway’.

She nodded. At least it was warm and there was plenty of light left. It wouldn’t be dark for a few hours. There was time to walk to Boston.

‘This is a horrible place to stay’ she said. ‘We can walk back. We can return tomorrow’

She looked up into his face. He nodded – but she could tell that he was probably thinking that they wouldn’t find a boat in the morning either.

********************************

They found an inn on the waterfront and sat in the room at the front that looked out on the boats. The tables were rough and there was sawdust on the floor. A few bearded fishermen sat drinking. They ordered beer – which was all there was – and sat looking gloomily out at the horizon past the forest of masts.

‘Who did you ask Howard – which boats?’

‘All of them around here. Maybe six captains or six sailors. I believed them though’

‘About what’

‘That they weren’t going to Holland. Most are fishing boats with no space for passengers.’

‘But this is a port. I went to the Dutch in Stathern to ask and they said Boston was the place to come to get a boat to Holland. All their wool goes that way’

‘There are some wool merchants here but they told me they aren’t sailing for a week. They’re waiting for wool to come from the farms’. He reached over and touched her hand and she smiled. She had been quite excited about going on a boat. She’d set her heart on it. Still, they’d get something.

‘Shall we go back to the town? I don’t think we can stay here’

She stood to take one of the big bags and scraped her chair back. In the window Howard saw a man passing. He was walking quickly. The man stopped and looked in at the window – at them. He was not bearded. He seemed young – but with the untidy hair that all fishermen seemed to have – perhaps because of the wind at sea.

The man took his face away and they saw him move on to the door of the inn. Then he was inside striding through the room, his heavy boots thumping on the wood floor.

He stopped before them and smiled standing very upright. He was quite short, and he had a sort of pleasing, youthful face. He might even be called baby-faced. He swayed back and forth, his smile fixed. His teeth were crooked.

‘You’re looking for a boat to Holland – to the Hook?’ His voice was weakly accented. It sounded like the south of England.

Howard nodded. He was sure he’d already asked this man, and he’d said no.

‘I thought that...’ said Howard.

‘Yes we thought that there’d be no room, but we’ve changed our mind. My name is Snap – my nickname. My real name is Richard. But call me Snap’

Snap looked about him. Howard thought there was something wary about the sailor. He was friendly but also watchful. One of the fishermen at the tables was turned to them, a smile under his beard.

Snap stared hard at the drinking fisherman who dropped his eyes immediately to look back into the depths of his beer mug.

‘We are sailing within the hour. I mean that. If you want a passage you have one. There’s even a cabin for you and your wife’

He smiled his crooked smile with his crooked teeth. He bent over to take the strap of Howard’s bag and lifted it quickly onto his shoulder.

They had no choice but to follow him out. They had their passage to Holland.

It was a small boat. Howard hadn’t seen it properly before, because he’d stood on the quay. When he’d asked before, Snap had been almost rude, wanting to get rid of Howard. But now the baby-faced man was embarrassingly helpful. He smiled a lot and scratched his head laughing absently mindedly. A few other rather shifty-looking sailors watched as the two travellers came on board. They watched for a few seconds and then went back to doing what they’d been doing, tying ropes, loading boxes. All over the deck Howard noticed bags of canvas tied together, but empty. Barrels of water were stacked at one end of the small deck. At the far end was a hatch that led below deck, and this was the way Snap took them.

‘The other men are dull, stupid – don’t mind them’ he said gesturing over his shoulder at the sailors. He seemed not to care if they heard him.

‘The skipper’s in the town. He’ll be here in a minute’ he mumbled.

At the bottom of a short flight of stairs was an open area, dark but for a candle and an oil lamp. It smelled foul, but there was a sweet herb smell too. There was a salted carcase of a pig hanging from the ceiling. There were beds along one side.

‘There’s a crew of three with the skipper and me. We sleep in there...’ he pointed at a pair of doors to the left. ‘This will be yours...’, and he took them to the door to the right.

‘But what is the cost’, said Howard. He was worried about the cost suddenly, seeing that they were being treated rather well. He was always wary of being charged too much.

‘You can talk to the master about that. Don’t worry. It’s cheap’

Through the door was a tiny space with two low bare beds and a curved wall that was probably the wall of the boat. There was a single circular hatch. There was enough room for the two bags and the two beds – and that was all.

‘How long does it take?’ asked Mrs Van Dijk. Her voice was high and wavering, tired.

‘Three, four days, if we’re lucky with the wind. Two or three nights’

Howard looked out of the window, having to crouch over, almost double. Outside was the hull of another boat, and below, perhaps only a few feet below, the brown water of the harbour.

He’d never sailed more than a few hours in a boat.

He turned to look at Mrs Van Dijk. She was tired after the long trip to the coast but not nervous about the voyage, just pleased they were on their way.

********************************

Under the two narrow bunk beds were more of the canvas bags that Howard had seen on the deck. There was damp in the corner below the narrow circular hatch. Howard thought that there were times when the seawater leaked through. He hoped that it wouldn’t happen on their voyage.

They put their bags on the hard planks.

‘It’s better than I thought it would be’ Mrs Van Dijk said. ‘If the boat was smaller we’d had have no room of our own. If the boat’s big also we won’t feel the sea too much’

But even the water underneath them in the harbour moved slowly and Howard heard the ropes creaking on the deck. The bad smell of the water in the quay leaked up through the floorboards.

They heard Snap’s voice and the thump of boots.

‘Would you like tea?’ he asked banging on their door. ‘On deck’ he said and they heard his boots retreat.

‘We should go Howard’ said Mrs Van Dijk. ‘I’m thirsty too’

They wondered through the dark lower deck and up the steps to the smaller upper deck. There was a lower part with about the floor area of the living room of their cottage in Earls Court, and two raised parts at the front and back of the boat. The mast – a huge column of polished blond wood – stood up from the back of the lower deck. Canvas sails hung limply from it and coils of stiff salty rope. Snap and another man sat together on a bench, their backs to the mast.

The other man was older, long haired, but with white hair that grew only over his ears. His head was otherwise bald and freckled and mottled brown from years of maritime sun.

‘Pickles – the captain of the Mabillard’ said Snap loudly, pointing at his companion with mock grandeur.

‘This boat is called the Mabillard?’ asked Mrs Van Dijk.

There were four big cups of tea on the bench. Snap held out two of the cups to the visitors.

‘This is the Mabillard’ said the older man. He narrowed his eyes looking up at Mrs Van Dijk. There was the faintest suggestion of a lascivious smile on the Captain’s lips. The captain didn’t offer his hand to shake, but simply looked levelly and rather coolly at his two passengers.

Howard took a sip of the tea and found it odd at first – nice but odd. It was slightly salty.

He looked into the cup, raising his eyebrows at the same time and Snap said: ‘Salty tea! The fisherman’s drink. Not made with seawater, but just mixed with the ubiquitous salt of the sea!’

‘It’s nice’ said Mrs Van Dijk under her breath.

‘We’ll leave within the hour’ said Pickles. He rose with his cup in his hand and looked amongst the sails. He shouted loudly to a man who was sitting with his back to them amongst the sail canvas. Neither Howard nor Mrs Van Dijk could understand what he shouted, but the man looked round and stood and started to pull in one of the larger ropes. Water sluiced off the rope.

‘Pulling up anchor’ said Snap. ‘Have you sailed before?’ He looked at Howard. There was some amusement in his eyes.

‘No’

‘Well don’t worry it will be easy. The weather is fine’

But even though the weather was fine, Howard became sick almost immediately in the little cabin. He couldn’t remember in his life ever feeling so sick. It was as if the world was constantly moving underneath him. At first he lay on the bed, trying to lie still, perfectly straight, looking up at the wood ceiling. But this was no good. The nausea was overwhelming. After this he tried shutting his eyes and imagining he was back in the cottage in the Vale, but then it was worse.

In the end it was a relief to be sick through the narrow hatch. Mrs Van Dijk got up to show him the catch that allowed it to be opened – but only just in time. Now Howard knew what the hatch was for.

For the first hours of the voyage, Mrs Van Dijk sat with him. Suddenly he had the selfishness of the sick man – who had no interest in anything but getting better and no desire other than getting better again. She stroked his forehead between his bouts of sickness, while he softly – and with great feeling – swore that he would never again sail in a boat, anywhere.

********************************

After dark, Mrs Van Dijk went up on deck. One of the men whose name she didn’t know was at the wheel. There was only a small breeze and the boat was remarkably stable. She couldn’t understand why Howard was so sick.

And the night was glorious. The sky was not black but grey – grey with stars. Only the sails were black. The light of the sky gleamed on the black water too. The sails and ropes creaked with the breeze but she could see from the water swiftly passing the gunwales that they were moving quick. The sky was faintly dark blue in the west where the sun had set. They were sailing due east. She sat on a bench and looked out to the front. It was magical – she could see ahead – maybe a low black cloud, maybe a coast. But it couldn’t be a coast – they were not so far out, not so many hours from England. She sat fascinated and tense with excitement hoping that no crewman would come up to the deck and spoil her quiet moment with the sea.

In the night, Howard groaned and coughed but was not sick again. She couldn’t tell whether he was sleeping.

It was long past midnight when she heard shouting. She wasn’t sure whether she’d been asleep or not. There was a sound of wind and the boat was moving more. There were shouts again, then talking from within their boat. She sat up and leaned over Howard’s sleeping body to look out of the hatch. She saw nothing. The sky was no longer grey with stars, but darker. She thought that clouds had covered the sky.

There was a creak nearby and a banging sound then a sudden bump that passed right through the boat. She froze, sitting upright in bed. Howard woke. She saw his sleepy head turn – he was listening.

‘Are you awake?’ he said.

‘Yes’

‘What was that?’

‘I don’t know Howard’

‘Have we hit something?’

There was shouting now right outside the door. Then very heavy boots walking on the deck right above them. There was a voice that they didn’t recognise, someone talking loudly.

‘I have to get up’

Mrs Van Dijk sat on the edge of the bed and in the tiny space pulled on her trousers and boots. It was warm and humid.

‘Have we hit something?’ said Howard stupidly; he was still not properly awake.

‘No Howard another boat has come alongside. I’ll get up and look’

He sighed and coughed. Was he going to be sick again?

‘I’ll come too – are you going up?’

There were two men in dark uniforms on deck. Pickles and Snap were there. They were in their clothes and both smelled of brandy or whisky. Mrs Van Dijk guessed that they hadn’t been to bed. The men in uniform were asking the two crewmen questions.

Snap seemed genuinely glad to see the two travellers from below the deck. He was half-drunk and he spoke loudly about how they had taken the two from Boston and were heading for Holland. There they would pick up other passengers to bring back to England. They did this often – trading in simple goods – wool, manufactured things. But their main business was passengers.

‘But we are legal’ said Snap, grinning at the officer. He swayed a little, holding a glass up-close to his face.

The two officers were quiet. There were lights off the far side in the darkness showing the position of the other boat. Mrs Van Dijk could just make out sailors moving on its deck, holding lanterns. It was some kind of military boat. She noticed that the officers’ uniforms were untidy. They looked tired. One had a large book in his hands. He opened it while she watched.

‘What’s the name of the boat’ asked the other officer.

‘The Mabillard’ said Pickles. ‘These two kind people are our passengers. We would have taken others but no one was about in Boston’

‘You’re taking them to the Hook of Holland?’

‘Yes sir’

‘You’re a bit far north aren’t you?’

‘It’s the wind sir. Also as you can see we have been celebrating and rather taken our eye off the sailing. But we’ll correct our course right now – this evening’

‘We’ll have to search your boat’ said the officer with the large book. The book looked like a ledger. He held a pencil at a name on a list on the open page. Probably it was the name of the boat.

‘I’ll lead you two gentlemen below’ said Snap.

He took the two officers down into the lower deck. They heard them talking and the thump of their boots.

Captain Pickles put his cup down and winked at Mrs Van Dijk exaggeratedly. He was probably more drunk than he looked.

Howard was sitting on a half barrel looking wretched. He was still coughing.

‘My husband has been sick’ she said without knowing why she’d started a conversation.

But Pickles seemed unable to speak. He swayed again and then sat down. He held his head between his hands.

Within a minute, the two officers were climbing the low stairs back onto the main deck. They looked satisfied that the Mabillard was not carrying anything illegal.

The senior man with the book picked up a brass lantern and they stepped up onto the gunwale and then across into the other boat. The other officer followed. Mrs Van Dijk noticed that the other official had a small pistol in his belt.

‘You’re free to go’ shouted the officer. ‘I would sober up though – if I were you. You’ll not be on the wide sea all night. Watch out for other vessels’

The lanterns on the far boat began to retreat and there was more shouting in the dark as the bigger boat began to pull away. There was a scraping sound and a bump and then they saw it move along side. It was much larger than the Mabillard – with a name in large letters and a symbol suggesting the King’s Navy.

Pickles and Snap went back to a bottle that they’d hidden and poured themselves more drink. The heat and humidity was surprising for a night on the North Sea, and Mrs Van Dijk didn’t want to go back into the cabin because it was so stuffy, but Howard still looked ill and probably needed to lie down. She had no intention of being alone up on the deck with Snap and Pickles.

********************************

It was a long night. Howard felt better, but now he couldn’t sleep. The nausea had gone but a powerful headache had taken its place. He couldn’t move without setting off a terrible pulsing pain that felt like his brain was expanding in his skull, more than his skull could accommodate. He tried to forget about it, and listened to Mrs Van Dijk’s breathing beside him, or the sigh of the water passing by the window, or the creak of the ropes and the old wood in the hull and the deck. He thought he heard Snap and Pickles walking around, laughing and even talking outside the door. Very late, when he was not sure whether he was awake or asleep, when the headache had finally begun to subside, he heard a click in the door and a low thud. This sound troubled him. He wasn’t sure why. In his sleep he thought someone had done something wrong, something bad, but he didn’t know why. He was either asleep or still suffering from sea sickness.

He slept on hearing the wind get stronger, and feeling subliminally that something had gone wrong.

Light pierced his eyes as he opened them. Light was coming straight in through the open hatch. It was bright sunlight. The wind was still strong and the whole boat moved back and forth. But it wasn’t a movement from side to side – which was what had made him sick. He lay feeling if there was any nausea, or any headache. Nothing. Why was he awake?

‘Howard – wake up. I don’t understand’

He turned. Mrs Van Dijk sat on the bed fully dressed, facing him. She looked very concerned.

‘I let you sleep. But there’s something wrong’

‘What?’ Nothing could be as bad as the nausea and the headaches. He almost felt glad. The morning smell of the sea was nice.

‘The door’s locked, Howard’

‘Are you sure?’

She sighed. ‘I wanted to go out to the privy but I couldn’t open the door’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes! Do you think I didn’t try the door?’

Howard sat up. He was still in his clothes from the night before, when the officials had boarded the boat. It had been the worst part of the night for him. He had felt terrible. He wasn’t even sure if he remembered the officials’ visit right. He’d been half asleep.

He pulled on the door. It was firmly shut. There was no give in the door either. It was very solid oak. He went to his knees expecting the headache to return and peered through the keyhole. The key was still in the keyhole on the other side.

‘It must be a mistake. They must have locked it by accident’. Then he remembered hearing something at the door the night before. The click of the lock.

He pulled at the door again. Then banged on it in frustration.

‘Did you go to the privy, Lotte?’

‘No of course not! Where could I go?’

He banged hard on the door. It was solid. He shouted.

‘Hey – the door. It’s locked.’ He banged very hard. ‘We need to get up’

Silence. He went to his knees again and listened through the door, and looked through the keyhole.

He went to the window and pulled on the catch and opened it slightly. He put his mouth as far out as he could, tasting the salt spray from the swiftly moving sea below. He bellowed into the wind.

‘Hey – open the door’

They must have heard that.

They waited.

‘Don’t worry. It must be a mistake’

This time he stepped back from the bed and pushed hard against the door with his shoulder and his body weight. The pain came back into his head immediately.

Footsteps came down into the lower deck. Howard hammered.

‘Open the door’ he shouted angrily.

Snap’s low cool voice came from the other side of the wood.

‘You’ll be alright in there. Don’t worry’

His voice was slightly malicious, maybe even amused.

‘We need to get out. My wife needs to get out’

‘No. You stay’

‘She needs to go out’

Howard banged furiously on the door. His head began to bang with pain. Once he got out he’d take that man Snap by his neck and...

‘Your wife can come out’

The door key scraped and the lock clicked. The door opened outward and Howard saw Snap’s foot just back from the door. Howard launched himself forward his head down low.

But he felt a terrible pain on his neck and a loud sound in his brain. The new pain was not the pain of headache. He fell to the floor and felt a splinter of wood enter his cheek.

********************************

He woke, face down in the bunk. This time he really felt terrible. His neck felt like it was broken. Mrs Van Dijk was beside him. He felt the boat move quite violently under him. But this time it wasn’t the sea that made him feel sick; it was the pain in his neck. He sat up and moved straight to the hatch and opened it so he could be sick again. He looked down into the swirling sea and a wave came up and splashed his face suddenly cold. Water poured in, and he withdrew his head, shutting the hatch. He gasped with the sting of the salt water. Then lay back on the bed.

Mrs Van Dijk sat beside him.

‘Are you alright?’

‘No. What happened?’

‘He hit you with something. He was standing behind the door. Does it hurt?’

‘Yes. Did you go out?’

‘Yes. He let me out to the privy then locked us in again. They’re keeping us locked up for some reason. They won’t speak to me’

‘Is there any food?’

‘He put bread on a plate and pushed it through. Do you want some?’

‘Yes, Lotte’

He sat up and his head began to bang with pain. This had been the worst two days of his life – pain and nausea. He would never, ever, come to sea again.

She held up a piece of dry bread on a broad white plate. He felt the back of his head. There was a bump and the skin felt hot. He looked at his fingers. No blood.

‘He didn’t cut you Howard. I looked. Take some bread’

He chewed the dry bread which seemed as tough as leather. Every time he moved his jaw, his head throbbed with pain. But he knew he must eat. He’d not eaten properly for days.

Mrs Van Dijk lifted a heavy brown jug to the bed and he heard a glug of water.

‘There’s enough water for a few days’

‘How’s the weather?’

‘I can’t tell Howard. Still sunny, but windier. We’ve been out of port for almost two days. We’re going fast with the wind.’

Howard laid his head back and looked up at the wood in the ceiling which was the boards of the deck above. He thought he could see the gleam of light between the boards, but he wasn’t sure. In a second he was asleep again.

‘Howard’

Mrs Van Dijk’s hand was on his forehead. He looked for the pain expecting it to come, but it stayed low, somewhere in his shoulders.

‘Where are we?’

‘I don’t know Howard. You slept for hours. How do you feel?’

‘Better. Can I drink’

He lifted the jug to his mouth and drank hugely. The water was wonderful – fresh and clear. For some reason he imagined it would be salty but it tasted so sweet. He couldn’t hold the jug up for long and he wanted to drink more. He set it down.

‘They’re moving around – on deck’

‘Who?’

‘The crew. I’m sure I heard them say something about us’

‘Where are we?’ he said again.

‘I don’t know Howard. It’s impossible to tell’

Howard looked out of the hatch. He thought he saw the sky bright behind the boat – in the direction in which they’d come. Was the sun setting in the west? So they were still sailing due east.

There was a thump at the door and it scraped open. Snap and the Captain – Pickles – stood in the dark lower deck beyond. Both carried heavy sticks.

Howard wanted to get up and fight, but when he tried to stand the pain was too great and he had to bend double. He thought he might be sick again.

‘Out’ growled Snap. He tapped the stick against his palm.

‘Where?’ asked Mrs Van Dijk quietly.

‘Don’t worry. You’ll be safe. We are just lightening our load’

Mrs Van Dijk began to tremble. Were they going to be thrown into the sea?

‘Madame’ said Pickles in a mock polite way, ‘don’t worry. We would not abandon you in the wide sea. We have brought you to somewhere safe’

Mrs Van Dijk stood up and pulled on her boots.

‘Come on Howard’

He got up and followed her out, his head still bowed low. The pain was huge. He felt it right down his legs and into his feet. Had they broken his back? But he could walk.

They blinked up on deck. The sun was going down, and the sails had been dropped. There was still a wind and the sea around to the west was milky and grey, but lit by glancing light. Mrs Van Dijk clutched both of their bags.

A rowing boat had been lowered and one of the nameless crew members was standing on the gunwale holding a rope.

The rowing boat rose and fell.

‘In’ said Snap.

Mrs Van Dijk lowered herself carefully down the frame of wooden slats on the side and into the row boat and Snap threw both of the bags in after her. Howard went down, grimacing with the pain of having to move. He sat in the boat his head in his hands. The crewman went down and then Snap. They cast off the rope and the crewman pushed the row boat away from the hull with an oar. Then with powerful strokes he brought the boat around and rowed hard pulling deeply on his shoulders.

Mrs Van Dijk looked into the setting sun for a few seconds, trying to decide what to do. The two sailors watched her fiercely, their faces slightly silhouetted by the brightness of the light. Howard sat motionless beside her. Snap still held the big stick.

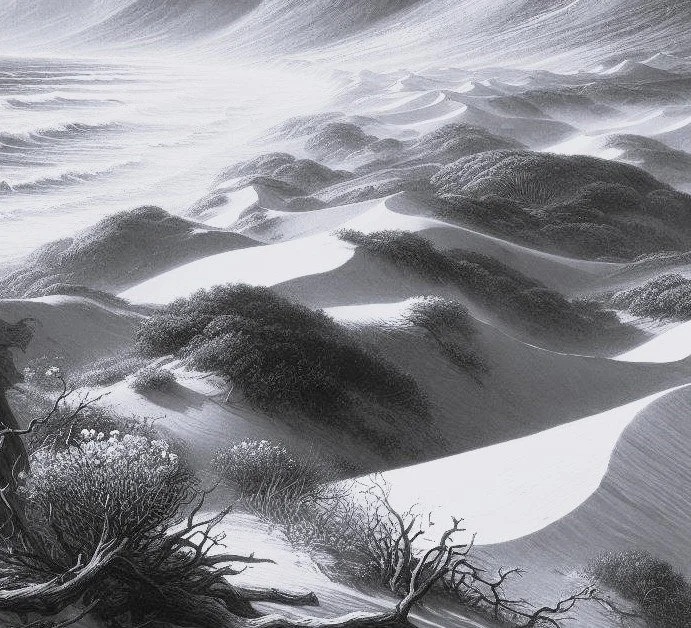

She turned at last, realising dully that their destination was behind her. The salt of the sea blew in her face, but past the dancing waves, just a small way ahead, was a line of dunes and dune grass silvery green in the sun.

PART II

They were told to get out of the boat where the water was shallow. But still the sea was cold. Mrs Van Dijk stepped out and the water went to her waist. The waves slapped against her. She held one of the bags above her head.

Howard stepped over the side. The pain in his head was less, or perhaps the shock of the cold water distracted him. Snap passed him the other bag.

He looked into Snap’s face expecting some kind of explanation, but the other just stared, his eyes empty. The crewman was already turning the boat around and pulling on the oars. The Mabillard was set back, huge and dark against the sky.

Howard waited, but no words came to him. The cold of the sea had made him mute. Mrs Van Dijk took his hand and pulled him. She had turned to the land feeling they had a better chance there. The row boat was already off and Snap’s back was turned. Not a word had been spoken.

‘Come on Howard – walk to the beach. We can change into dry clothes’

‘I don’t understand’ he said dully looking at his feet in the clear water.

‘Neither do I’

It was a wide beach but not in a bay – it was convex outward so it felt like they were on an exposed point. The sand was littered with drift wood and debris from boats, pots and planks, part of an old chair. There were shells everywhere, pink and blue, some partially buried, some upturned and filled with sand.

There was wind blowing along the shore but the sand was too wet to move. They wondered slowly up the beach into finer, drier sand that was cream in colour and rippled into long waves. Thin delicate grass spiked up through the sand, and there were traces of birds’ feet, mice and rabbits. There were no human footprints.

Then the rippled sand folded upward into a line of dunes. Coarse dark grass was combed back against the wind and sand was blowing in white veils like smoke over the ground.

They followed a passageway between two big dunes and immediately the wind was gone, and sound was deadened by the sand. It led up into a small platform behind the head of a dune but up quite high. It was slightly lower in the middle of the platform with tall grass around the side, like a shallow bowl. The sand was warm and there was no wind.

Howard was already exhausted. He sat heavily on one of the bags and felt behind his neck where the pain was worst. It was still warm and moist. His fingers had a bit of blood.

‘Did you bring the water?’ he croaked.

‘In the bag’

Mrs Van Dijk went up to the high point of the dune leaving the bags. It wasn’t the highest dune, but it was amazing that they were all so similar – all about the same height. There were other dune ridges further in from the beach, but not as high. She stood looking at the sea, and the wind blew her hair out behind her. The water was shiny like a polished shield, and at its centre she could see the small spiky outline of the Mabillard. It was hard to tell, but she thought it was sailing back out to sea. To her left the great arc of the beach was rimmed by the dune ridge, as far as she could see. Inland the shoulders of the dunes dropped down into rolling grasslands. There were no fences or hedges. Some of the grasslands were scarred with creamy white where the sand showed through. She thought there were dunes beyond the grasslands, but she couldn’t tell. The sky was grey in the east. Perhaps it was raining out there. Wherever ‘out there’ was.

She let herself slide down the dune to the hollow where Howard still sat on the bag. She felt the sand fill her boots up. But at least it was warm

She was always very practical at these times. Howard had not done anything about the drinking jug so she took it out for him and laid it on the sand by his hand. She opened one of the bags, which was his, and took out trousers for him and another pullover. They would have to sleep in the dunes, so he’d need to be warm.

‘Howard’ she spoke almost roughly. ‘Drink some water and put these warm clothes on’

He got up like a child scalded by his mother and took the trousers and changed. He looked terrible – with his white legs and his battered face. He put a pullover on and sat back down on the bag. His face was white under his angry dark hair.

‘This is better than the boat’ she said.

He didn’t say anything but took the water jug and drank deep. She wondered how much water they had, and how much they might need.

He seemed immediately to think the same.

‘Any sign of people – a village? What country is this?’

She shook her head. ‘I can’t see anything – only dunes and grasslands’

‘Is there wood for a fire?’

‘I’ll go and look. You sit and keep warm. You’ll feel better soon’

She thought she should change her trousers but already they seemed to be drying. The warm wind dried everything. The air was like a balm – perhaps it was the placid sea.

She walked down the steep inner slope of the dune feeling the sand collapse underneath her. It was warmer down here, and the marram grass grew very tall, almost head height. There were lower mounds of sand and then the grassland began. But it wasn’t really grass – it was more like spiky succulent plants growing close together in a mat. She thought she should know some of the names from her book The Flowering Plants of Northern Europe. There was some sea cabbage and sea campion. There were flowers here and there and rabbit holes and smears of cream and yellow sand that had been dug out.

There was a pile of very dry wood from a long dead tree. It was grey and bent into curves like bones. She lifted it and it was light from years of rotting and sunshine. But still it would burn. There was more further on. But no water.

If they had had food, it would have been a nice place to stay.

She turned and started to walk back to the hollow in the dunes. She thought she would change her clothes before the dark came.

********************************

Rather than stay up in the dunes, she realised it would be better to go down where the wood was. Though it was warm now, it would soon be cooler. It was always better to be near a fire, and she’d have to carry to wood if they camped up in the dunes.

So she told Howard to take his bag and carry it down. Near to the pile of wood, there was another low hollow, this time ringed with succulent grass and flowers. There were animal burrows but they looked old. She didn’t want to disturb a fox or a badger in the night.

In the hollow there was a place to sit on the short wiry grass and if the wind blew they’d be sheltered. For now it was still.

She dragged the grey wood from the pile into the hollow and went looking for more, before it was completely dark. She was also looking for human signs, footprints, or anything human at all. Though they were out of the dangerous boat, this was not a place that they could survive for long.

Not far from the hollow she found another low place where the grass was taller and the ground damp. In the centre was a mass of tall reeds that surrounded a shallow pool of clear water. She put her finger in to taste it, expecting it to be salty. She was surprised to find it was fresh with only a slight salt taste. They’d not drink this yet, but if they had to she would come and fill the jug. She’d have to make a decision in the morning whether to stay or move on. It depended on how well Howard was. He wouldn’t be able to walk far in the state he was in. She climbed back up to the edge of the hollow and looked what she thought was south. She had the impression that the land on which they had alighted, this windswept coast, was more continuous that way, and that they’d have better luck walking along the beach southward.

In the dancing light of the fire, Howard looked better. He no longer held his head down. He’d drunk a lot of water but now he was hungry. Mrs Van Dijk found some oatcakes in her bag that she’d completely forgotten about. She’d carried them all the way from Earls Court. They ate them looking into the fire.

In the night Howard murmured in his sleep ‘where are we?’ and started to get up, so Mrs Van Dijk put her hand on his chest.

‘Don’t worry. Sleep Howard’

He lay back and didn’t reply and his deep breathing suggested he was asleep. But Mrs Van Dijk was disturbed. She propped her head up on the folded coat that was her pillow and looked around. It was deep night. The fire glowed at their feet and a single wisp of smoke rose. The sky was misty but stars in grey patches showed low in the east. Perhaps the bad weather she’d seen earlier in the day had cleared. She listened and thought she heard animals moving around – small digging noises and the rapid pattering of feet.

She had an idea to look for light as sign of human settlement, so she got up trying not to disturb Howard and retraced her steps to the high platform behind the big dune. The sand was cold now and harder to climb – each upward step pushed a mass of sand down under her boots – but she got to the top. The wind was still blowing off the sea from west to east. This was why they had travelled so fast in the boat, she thought. After all they must have crossed the North Sea. They must be in Holland or Germany.

She climbed to the highest point of the dune. The sea was a dark part of the sky but she could dimly see white lines forming on its surface, which she thought were breaking waves. The sky in the east was clear but there was nothing distinct in the land in that direction. There were no mountains, there was no light. To the north it was dark. To the south where she thought they should walk in the morning, there was more to see, perhaps because the dunes that stretched for miles, were quite light even under a moonless sky. But there were no points of light. They were alone.

She went back to the hollow and got under the one blanket that she shared with Howard.

Howard woke her, his face looking down into hers and bright sunlight around. He was grinning.

‘My head’s better’ he said.

‘I’m glad’

She lifted herself onto her elbows and blinked in the bright light. The sun was warm on the dark blanket.

‘I found water nearby’

‘There is some water’ she said sleepily.

‘...and blackberries!’

He dropped a handful of blackberries into the blanket over her lap, sitting down heavily next to her. One or two were red, but most were glossy and black, quite edible. His fingers were purple with blackberry juice. He’d probably eaten a lot.

‘There’s a bank of brambles – a huge bank – over there. I’m not even hungry now’

He seemed happy. His face was red and his beard had begun to grow.

‘So do you know where we are?’ he asked.

‘You asked that in the night. I don’t know where we are. I think we came east with the wind, so perhaps we’re in Holland or Germany...’

‘It seems like England. There are coasts like this in the east.’

She tried one of the blackberries. It was very sweet. The seeds rubbed on her tongue as she swallowed it.

‘We can’t have gone back to England’ she said.

‘Why did they drop us here?’

That was the big question, but neither of them had any idea why.

********************************

‘Which way shall we walk?’ said Howard, lifting the bag onto his shoulders.

‘I thought this way’ she pointed down through the dunes. ‘I think it’s south’

Howard looked down at the place where they’d camped. There was nothing but cold ashes and disturbed sand where they’d slept. It was odd though – and satisfying – that they hadn’t left anything. They were truly travelling light.

Mrs Van Dijk said: ‘we should walk along the beach’

‘Why Lotte?’

‘So we can see far ahead, also so we can see footprints’

‘Have you seen any?’

‘Not one – except mine and yours!’

So they climbed back up and through the dunes onto the big beach. It was so bright that they had to screw up their eyes to see. The sun was shining onto the sea from the east and it was blue, and dark, almost violet, far out.

Their footprints of the day before were just lines of little depressions, leading to the water. They’d lost their form overnight.

After a long while walking they thought they could see a building or a boat – a dark disruption of the sand horizon in front, but as they got closer they saw it was a huge trunk, scoured and stripped by the sea, half buried. Crabs scurried around it but disappeared as they got closer. They sat on the wood looking south, their backs to the long stretch of beach they’d walked down.

Howard got the jug of water out.

‘I filled it from the spring this morning. It’s a bit salty but tastes alright.’

They both drank.

‘I forgot why we were coming to Holland’ said Howard suddenly. ‘To see the publisher!’

Mrs Van Dijk nodded. At least it was pleasant sitting on the big trunk. The wind was weak and the sun shone on her legs. She thought she’d take her boots off and carry them – and roll up her trouser legs.

‘I’m going to be late for the meeting in Amsterdam’ she said.

‘Do you mind?’

‘Not really. They’ll understand when we tell them. That we were kidnapped’

‘They didn’t ask for a ransom. I wonder where the boat is – the Mabillard?’

‘I looked yesterday when you were lying in the sand. They were sailing back out to sea’

Howard picked up his bag again.

‘Shall I carry yours?’

‘Yes – if you can. I’m going to take off my boots and tie the laces together, then hang them over my neck’

They walked for a long time, past the time when the sun was high. The beach hadn’t changed much. It was hugely wide, perhaps a hundred yards from the sea up to the first dunes. With the tide out, that distance was even greater, and a huge expanse of shiny flat sand was revealed. But the tide was coming in now and they walked on the softer sand, which made it more difficult to make progress.

They’d not seen anything more than the trunk in the sand, the thousand little crabs and here and there shells and dead and drying fish. Howard was getting so hungry that he thought he would eat a crab raw if he could catch one.

So they walked from the open beach into the dunes again. Even though they’d gone many miles, the land was like it had been that morning. It could have been the same place. The same line of dunes, the same interior of grass plains and meadows, the same sandy burrows and flowers. Howard wondered if they’d walked anywhere at all. Between two big dunes they sat down.

Mrs Van Dijk was now very tired. Sometime in the afternoon she’d put her boots back on because her feet had begun to hurt. Now she ached all over from walking. She was hungry too.

They sat in the shadow of the dune and she suddenly felt cold. The sand was cold. She realised she didn’t want to spend another night out.

‘Lotte. I’ll look around. I’ll get some blackberries’ he said.

‘Howard’ she said sighing heavily, ‘we can’t live on blackberries’

‘I know’. He touched her cheek. ‘Don’t worry. I’ll find water and some food. Sit in the sun’

He took the two bags and set them on the slope of the dune and encouraged Mrs Van Dijk to sit. She sat with her back on the bags facing out to sea looking miserable.

He went off into the dunes, looking for dark masses of brambles or anything else. Rabbits were very common – as he came to the top of a small dune ridge, through the marram grass, they must have seen him and they scattered into their burrows.

He looked around, surveying the green backs of the dunes, then dropped down a slope onto the grassland. After a few minutes he came to a mound of sand that must have been made by digging animals. There was a bramble growing near it with a branch rich in blackberries.

Under the branch in the fine cream sand was a fresh human footprint.

********************************

‘How long before dark?’ he asked when he got back.

‘Not long Howard’

‘I found a footprint’

‘Really?’ she brightened. ‘Where?’

He held out blackberries that he’d collected in his hat. ‘It was under the blackberry bush’

‘Where did the prints lead?’

‘I only saw one’

She looked quizzically at him her brows knitted together.

‘It was just a little patch of sand with a footprint right in the middle’ he explained. ‘It didn’t go anywhere’

‘But it’s a good sign’ she said. She took hold of the water jug and drank.

‘Do you want to walk some more, or shall I look around?’

‘Let’s walk’ she said.

So they returned to the beach, but now they walked looking down at the sand searching hard for footprints. There were none. The shadows began to lengthen as the sun went down into the sea and the sand got rapidly cold so Mrs Van Dijk stopped and put her boots back on. She rolled down her trousers dusting the sand off her knees.

The dunes got lower to their left and at last the beach started to curl away to the east. A vast expanse of sea opened in front of them and the dunes fell away to flat land. To their relief they saw a fence post driven into the sandy soil. There was no fence leading off from it. The grass was mixed marram and a softer finer grass that cattle or sheep could eat. They wondered if it was cultivated land, or at least land that had been prepared for grazing. Looking ahead, the now flatter land had no dunes. Beyond the big expanse of sea there was nothing. It was just sea all around and a tiny flat shelf of land. The sky was like a huge reflection of the sea. Howard felt like it was like walking along under a huge mirror.

They sat by the fence post. Strangely it gave them some kind of solace – as a sign of human habitation, or a sign that someone once did live on the grasslands. Howard had been wondering for hours if they had actually slipped back in time as well as being kidnapped, and that they were stuck, marooned, in a place far from their own time, as well as their own place. But this fence post, grey and weathered, showed them that they were not the only humans on earth. It was like the only fixed point on a strange map.

They thought they would camp by the post, so Howard unloaded their one blanket. The air was still warm, but there was no wood around, so this night they would have to survive without a fire.

The dark came quickly spreading across the sea from the west. In the east when Howard stood up a single light winked on and off somewhere across the grassland. He watched but said nothing, not being sure of what he’d seen.

But then it came again, faint and yellowish. Perhaps a few miles away.

He reached down and took Mrs Van Dijk’s hand saying nothing. They started to pack their bags again.

PART III

There were low houses of a kind they’d never seen before, just back from the sand. Lights glowed from two of the houses and a larger structure like a hall. The sand was criss-crossed with thousands of tracks. In the shadowy fields and meadows there were sheep and goats, and a single large horse. Plots of vegetables neatly planted and with strips of paper designed to scare the birds, were squeezed between the meadows.

They stood in the sand at the edge of the village in the half dark. No one came out to greet them, so they assumed they hadn’t been seen. The wind filtered through the paper streamers and sighed in the grass, then a sound of singing came from the low hall. Two dim lights glowed in its low windows. The singing was high and tremulous – like the singing of women together. It was a slow song which rose and fell. A single voice was louder than the others.

They left the sand and followed the grassy path. The singing became louder. Up close the houses were very strange. Their walls were low, much lower than Howard’s height – and the low roofs were heavy with grass and moss rather than thatch. It seemed as if the roofs were little meadows. The windows were small and tucked just under the roof, and the doors were narrow and low, but painted bright.

These were not houses of English style, nor of Dutch. Not for the first time they wondered where they were.

They waited until the singing had finished and then climbed the two steps to the door of the hall and knocked quietly. There was whispering from within and a face appeared at the door, which had opened only a small distance. A brown faced woman looked at them, wisps of grey hair fell across her broad cheeks. Howard thought she looked vaguely like a mouse. She had large eyes with large brown irises, and the white around was very small. She was short. She squinted up at Howard. Maybe she was short-sighted as well.

She said something in a language they didn’t understand. It was guttural but had the sibilant sound of German. But it wasn’t German.

Mrs Van Dijk smiled her friendliest smile and said hello first in Dutch and then in German. The woman still stared. She blinked. The door opened a little wider and the woman called behind her. Another woman appeared. Howard could see behind a candlelit wooden table and wood walls. It looked warm inside. There were women sitting around the table.

The new woman was taller and more confident – with a thinner face and pale blue eyes.

She spoke in German rapidly. Neither Howard nor Mrs Van Dijk understood.

‘She thinks we’re German’

‘We are lost’ said Howard, speaking slowly. The woman stared. It made no difference how Howard spoke. She didn’t understand.

Howard made a gesture with his hand rubbing his stomach. He immediately regretted it. He was just hungry and hadn’t thought it was rude.

But the woman immediately understood. She stood back and said something in a guttural sibilant language, then walked past them briskly onto the step.

She gestured for them to follow and she took them along a path at the front of the low houses to the last house. She pushed the door open. Candles were arranged inside. There was another large table and a pot on a fire. Plates were stacked by a large washing bowl. There were sacks of potatoes against the wall and fruit on shelves. There was a smell of stew or soup.

She showed that they were to sit and two plates were put in front of them, and a jug of water. The woman who was brisk in everything, poured a broth onto the plates which was lumpy with potatoes. It steamed into their faces. It smelled wonderful.

They nodded their thanks and plunged their spoons into the food. The woman smiled faintly, watching them with her hands on her hips. She seemed momentarily maternal.

She turned to go to the door.

A few minutes later, as the food began to fill their stomachs they heard the singing resume in the little hall.

********************************

After eating they went to sit outside. The thin-faced woman didn’t come, and the singing continued in the hall. The music was slow and controlled, sad and restrained. There were times when the voices climbed high and plaintive, and the one dominant voice became very clear. But there were gaps between the songs, and silence. In those silences the wind was the only sound, and the distant sea whispered. They saw its white waves curling out in the bay.

After a long time the singing faded and the singers came out, carrying lanterns and candles.

They were all women, dressed similarly in shawls around their shoulders and long skirts. The older women had white head scarves that concealed their hair. They talked amongst themselves and the thin faced woman came to the visitors again. She was stern and authoritative and led them away from the main houses on a continuation of the path to a small hut amongst the vegetable patches. It was the same design with a low overhanging roof on which grass grew freely. She ducked her head low to enter and gestured for them to follow. There was small bed inside and a single table. There were small windows at the back and one facing the front, towards the dark sea.

She lit a candle and yellow light sprang onto the wood walls. Howard looked up at the ceiling curiously, expecting to see a mass of roots, but there were clean solid planks. They hadn’t noticed that the woman carried two blankets under her arm. She placed the blankets down patting them in a maternal way and nodding. She said some words in her strange language and left them. Howard watched her wander back to the group. The women hadn’t dispersed. He thought he heard them talking quietly, perhaps about their new visitors.

‘It’s nice’, said Mrs Van Dijk sitting on the folded blanket. ‘Not cold. And they were very kind’

‘It’s a strange place’

‘Some kind of religious place. I think the songs were hymns – you know – religious songs’

They laid down without undressing. Howard listened to the wind and the distant waves and slept.

It was white light in the morning and Howard thought he was back in the dunes. But the sun was shining right into his eyes from the white window. Mrs Van Dijk was curled beside him in her trousers and big pullover, fast asleep. Her head was on her hands which were pressed together like she was praying. She looked peaceful.

He went to the window and saw the sea immediately and the tall grass waving outside the front of the hut. There was a woman on the beach walking slowly head down, occasionally picking things up.

The air was salty, washed clean by the wind. The window rattled.

There was water in a jug by the door. He picked it up and poured it into two cups on the white table. He took a cup to Mrs Van Dijk waking her.

‘Water, Lotte’

She opened one eye and withdrew her hands, smiling and sighing.

‘How is it?’

‘Very nice. One of the ladies is out collecting on the beach’

‘Is she still there? Go and look’

He went to look but she wasn’t there. The sea met the sand in two big swipes of colour, blue and cream.

When he looked around Mrs Van Dijk was back under the blanket.

********************************

One of the women came to the hut and knocked on the door gently.

They hadn’t seen her before. She was round and fat with a pink jolly face. She wore a scarf over her hair that cut across her forehead rather severely. But she was very cheerful. She stood at the door when Howard opened it, holding a spade in her hand. She nodded furiously and pointed over behind the houses. She babbled in the strange language. Maybe she didn’t know that they didn’t understand.

But then she led them to the house that they’d eaten in the night before along the grassy path. The sky was big and streaked with thin cloud. It felt cooler than the previous day and it wasn’t so humid.

Again there was a stack of bowls by a washing bucket, and on the table two more bowls of porridge. Steam rose from the bowls.

When the woman left, they tried the porridge which was salty rather than sweet.

‘They must eat very early’ said Mrs Van Dijk between mouthfuls.

‘Why?’

‘Because all their bowls of porridge are almost dry – can you see? They probably get up very early. Did you hear anything this morning?’

‘No. I was asleep, and in our hut you can only hear the wind. I like it though’

Howard looked into the bowl and saw that he’d already finished the porridge. It had been a strange recipe – salty and thick. Not like English porridge.

‘What did the woman mean about the spade?’ asked Howard.

He found out very soon. Three women arrived at the hut. One was the jolly lady. They were leading an old donkey and a cart with ancient wooden wheels. The jolly lady gestured for them to come, and they set off on a track through long grass leading away from the houses inland to the east. It was so completely flat that nothing could be seen of the land. There was grass that crowded in around them, and above a vast sky. The world was simply green and grey blue.

The women talked and laughed leading the donkey, and spades rattled in the cart. Howard and Mrs Van Dijk walked behind the ladies, wondering where they were being led. The track looked to Howard that it had been designed entirely for the cart, worn by countless journeys of the women and the donkey. But the track seemed to lead nowhere. Soon the deep ruts made by the wheels began to get wetter and the ground underfoot was softer and spongier. There was slight upward incline, almost imperceptible.

The cart came to a bank of what looked like cut soil and the women wheeled it around and unharnessed the donkey, tying him to a pole. They women unloaded six spades and passed them around. They were still talking cheerfully. Howard had never heard such talkers – but perhaps he was more aware of their talking because he couldn’t understand what they were saying. The language was rapid, but consisted of lots of slurred sounds, some of which he was already able to recognise. He wondered if they were parts of words.

The bank of soil was waist height, damp and shining in the sun, and there was a cleared area of flattened soil in front so it looked like the bank had been cut back in slices.

Then he realised what it was.

‘Peat. It’s peat’

‘What Howard?’

‘Soil filled with wood and plants. If you dry it, it burns – like coal’

‘Ah yes!’

‘It’s only found in wet places, high up places’. He picked up one of the spades. It was peculiar – light and long with only a narrow shoulder. The cutting part – the blade – would only make a narrow cut.

The spade felt light in his hands and he turned it then plunged it into the soil at his feet. It went in easily.

The women noticed and smiled in encouragement, nodding. Their voices rose and they talked loudly amongst themselves. They seemed to approve of Howard suddenly. He smiled back shyly. But he felt good that he understood at least something, and could do something of use.

‘You’ve made friends’ said Mrs Van Dijk, also grinning.

Howard knew how to use a spade but this work was difficult. The women lined up at the face of the peat and cut down in wet slicing motions with the narrow spades. Then they would lever the cut piece out cutting through the base to make a piece of peat about the size of a loaf of bread.

Howard copied the women. They were remarkably adept at cutting, starting with a big heavy chop; arms raised high and using the weight of their shoulders to push down. Then the swift horizontal cut to release the loaf of peat.

The women chattered. He was frustrated at first that he was slow, and Mrs Van Dijk even slower. Mrs Van Dijk found the cutting very difficult and soon had rather bad blisters on her hands. She sighed stretching her back and looking up at the sky.

The women began to sing after a while a strange song that was more of a rhythm than a melody. They took turns to sing some little phrase or shout something out. The rhythm was the same as the cutting, and the chop and slap of the spade blades had a place in the music. The exhaled breath of the cutters became rhythmic too, making the music seem heavy and primitive – not like the ethereal spiritual music of the night before. Sometimes in the strange rhythmic song, the women would laugh uproariously at something one of them had said or sung.

This was all foreign to the two visitors. Howard didn’t mind because he felt grateful to the women – for their hospitality – and so he wanted to show that he was useful to them. But Mrs Van Dijk began to feel a little excluded. Howard was foreign because he was from a place far away – and a man – but she was only from far away. Also she couldn’t cut the peat well, it hurt her shoulders and her hands and she couldn’t find the rhythm of the song in her cutting.

They stopped after a long time, and water and cake wrapped in white cloth were passed around. They sat in the long grass next to the face above the cut peat that shone brown like chocolate in the sun, eating the cake. It was some kind of potato cake – heavy and salty but nice. Cutting peat made you hungry.

One of the women saw Mrs Van Dijk’s red hands and squawked like a bird in sympathy, taking her hand in her own, opening up the palm.

‘Ah’ she said.

The woman’s hand was heavy with callouses and hard like a man’s. She’d been cutting peat for years. The woman was plump – like all the others. Her kindly face was lined from years of the wind in the dunes. Her brown eyes looked into Mrs Van Dijk’s. She stroked Mrs Van Dijk’s long fingers admiring them.

‘Sorry’ said the woman.

Howard heard the English word too and looked up.

‘Sorry’ said the lady again – indicating the blisters on Mrs Van Dijk’s hands.

The other ladies said sorry too. But the sound of the word was quite foreign, like they were repeating it without understanding its meaning.

********************************

It was difficult to tell how long they had worked at peat cutting. Howard and Mrs Van Dijk were used to hearing the bell in the tower of Earls Court church but here there was nothing. But when the sun was high, the women stopped and began to stack the peat in neat rows on the floor of the cart. They took great care to stack the chunks of peat upright rather than flat. The donkey was re-harnessed and slapped hard on the rump to begin the journey back.

Howard and Mrs Van Dijk walked behind the cart, exhausted. The women were also quiet on the way back. Once or twice one of the women would look back to see the visitors, but in general they kept to themselves. Except for the word sorry, nothing had been said between the women and their visitors all day.

‘Are you worried about the meeting Lotte?’ asked Howard.

‘The one in Holland? No not really. I was certain that the crew of the Mabillard would throw us in the sea. You know the night when you were sick, after being hit...? That was terrible. I’m just glad that we’re alive’

‘It’s a nice place, this’

They could hear larks calling high above in the blue sky that was streaked with high feathery clouds. Howard realised that the larks had been singing the whole time that they’d been working, but he’d not really noticed them.

‘Who do you think they are?’

‘The women? Some kind of religious community. We could stay here a while and then try moving on. Even though they don’t speak English or Dutch we’ll have to try to understand where we are’

She laughed. ‘It’s strange – it’s the first time I’ve been in a place and not even known the country or the language’

‘When we leave, we’ll have to give them some money for the food and their kindness’

‘We must try to talk to someone – one of the women. We have to find out where we are, and find the way out. Did you notice any path or track – any large track?’

‘No, nothing. In fact this is the only track out of the settlement. The place is completely without a road’

‘How strange’ murmured Mrs Van Dijk

They went to the large hut in the afternoon after eating the same kind of broth they’d had the evening before – potatoes and turnip. The tall woman with the thin face was sitting on a bench under the overhanging roof, sewing. Her hair was covered unlike the evening before. It made her face even more striking. Her nose was quite narrow and sharp and her light blue eyes were like ice. She looked quite unlike the other women.

She gestured to them to sit. Mrs Van Dijk turned to the woman and put her hand to her chest saying Mrs Van Dijk, then pointed to Howard saying his name as slowly as she could. The blue eyed woman nodded, putting her sewing down and said name was Karen, pronounced with a long ‘a’.

‘Which country is this?’ said Howard.

Karen looked blankly at him.

‘No Howard, it won’t work. How can we ask?’ Mrs Van Dijk said.

There was a patch of sand in front of the bench. She got down on her knees and tried to draw the outline of Europe in its soft loose surface. She spent some time on the boot shape of Italy and then rounded Spain and France and made the triangle shape of Britain. She tried the countries of the North Sea up from France to Holland and Germany. She pointed at Britain and touched her own and Howard’s’ shoulder.

‘England’ she said.

‘Ah’ said Karen and bending over pointing above the map that Mrs Van Dijk had drawn, to the north of her uncertain line, into nowhere.

‘Danmark’ she said. ’Danmark’

‘Ah’ said Mrs Van Dijk and Howard at the same time. They sat back thinking, resetting their minds to the right place.

‘Denmark’ said Howard looking out over the sea. ‘We must have come further, and due east’

Karen was smiling, looking less proud and formidable than before. Perhaps the two visitors now seemed more human. Living in this isolated place, it must have been disturbing to have strangers appear from nowhere – straight from the sea.

‘Where is Kobenhavn?’ asked Mrs Van Dijk. ‘Kobenhavn?’ she tried to say the word differently not knowing how to pronounce it

Karen looked blank but then nodded ‘Ah Kobenhavn!’ She pointed over the grassland to her left.

She rubbed out the indistinct Europe in the sand and made the upright shape of Denmark on its own, like a thick thumb. She made a spot in the sand in the north of the thumb. ’Kobenhavn’ she said again.

Then to the left of the thumb she drew a small oval very carefully, saying ’Torshavn’.

She stood and pointed at the little disc and said the name again: Torshavn. Then she pointed to the ground.

‘We’re on an island’ said Mrs Van Dijk. ‘...and that’s why there are no roads leading anywhere else’

********************************

In the afternoon, one of the women appeared with a wheelbarrow of dark peat wheeling it over the short grass to the hut.

Howard came out to greet her. He remembered her as one of the peat cutters.

The woman smiled – and uneasily said something that Howard didn’t understand. Mrs Van Dijk came out.

The woman said the words again, and then letting go of the handles of the wheelbarrow she made a sign wiggling her fingers and bringing her hands down either side of her head. She pulled her thick jacket about her and pretended to shiver.

‘The weather’s going to change. It’s going to rain’ said Mrs Van Dijk slowly.

The woman showed them the stove at the back of the hut and the metal lid that opened. Inside were the ashy remains of burnt peat, white like chalk dust.

The peat the woman had brought was dried, not like the fresh peat of the morning. It was much lighter and rough to the touch. In its texture you could see the remnants of plants and woody fragments that crumbled away if you scraped the surface.

She showed them how to load the peat into the stove and she left a box of matches.

When the woman had gone they sat under the overhanging roof and talked about what they should do. Of course they would have to leave, perhaps tomorrow. How could they get to the mainland? There must be a way to get to the mainland. After all the women – the sisters, for they seemed to be part of a religious community – were able to get things like matches. They had stoves too and building materials – so it must be possible to sail to the mainland. They would ask Karen tomorrow.

‘But the weather will be bad tomorrow’ said Howard.

‘Just a bit of rain perhaps. We can ask her and we’ll find the place where the boats come. It’s too shallow here for a boat to come in’

But it wasn’t just a bit of rain. In the night the wind built up slowly into a rush that sounded like flooding water, and then into a moan, then into a howl. The sound woke both of them, huddled together in the small bed, suddenly cold. Howard felt the air moving in the hut and heard the creak of the windows as they were pushed at by the pressure of the air flying off the sea. The wood logs that made up the walls leaked wind and cool air came under the door in a rush. His nose was cold.

‘Are you cold, Lotte?’

‘A little bit. Is it late?’

‘I don’t know’

The wind came in brutish rushes and seemed to be trying to push the front wall of the house down. The roof moaned and whistled above them. Howard looked up nervously at the wood supports – for signs of movement – but there was nothing. Perhaps this was why they planted the roofs with grass, to weigh them down? To stop the roofs from blowing off.

He couldn’t sleep and so got up. The wind seemed to have lessened, but he felt the freezing stone floor on his bare feet, and the damp. He looked through the dim window, out toward the sea. He thought the light was about to come in the east. The window had stopped creaking but rattled a bit. As he peered through, the first rain came, just a few drops propelled by the flowing air, hitting the thin glass like grains of sand. They ran down its surface. Then more rain so that in a minute the surface of the glass was pouring with water. He heard the deluge on the roof, even through the wood and the grass. Cold came too with the rain – he felt it diffuse through the room from the outside. In the faint light he saw the long grass outside being held down by the rain.

He went to the stove and put some of the peat inside with soft dry grass as tinder. He lit the grass and it flared up with yellowish light. He saw Mrs Van Dijk watching him from the bed.

‘It’s raining’ he said.

‘I know’

He spent a long time encouraging the flame so that the corner of one of the bricks of peat began to flare red and glow. He felt the front of the stove warm up. Then seeing a trickle of water come under the outside door, he put a box up against the wood and immediately some of the cold draft was gone.

He went back to the bed and got under the blanket.

A massive front of rain hit the hut and sprayed the window.

He thought it unlikely that they would move on that day. But he would wait to see what Mrs Van Dijk said.

********************************

As day came, the onslaught of rain didn’t change. They got up and dressed and sat by the stove and Howard sometimes went over to the window to look out. He’d never been imprisoned before by the rain, but this was not like an ordinary storm. Once in the late morning he moved the box and opened the door, and the force of the wind almost knocked him over. The wild air whipped into the room making the stove flare and the sheets on the bed billow up. He got a face full of cold rain in a second before squeezing the wind back out. He stood with his back to the door, trying to smile.

But now hours later he was feeling trapped. He looked out at the other houses through the streaked window and saw no one moving. Thin smoke was smeared horizontally from the chimney pots above the grassy roofs. The women were burning peat like they were. It was the only way to keep warm.

‘Peat only collects in wet places’ he sighed. ‘Perhaps the weather’s like this most of the time’

It looked very different out there. The grasses were greener after being washed so thoroughly and the sea was very dark, like a black band with white lace of storm waves. The clouds were just above the beach, angry and grey like cliffs above the sisters’ houses.

‘Come and sit by the stove’ said Mrs Van Dijk. She was sitting with her feet up on the side of the stove, where it was warm. She was looking at a book she’d brought. She didn’t mind sitting for a while: she was aching from the peat cutting and her hands were still sore with blisters.

‘The women here must be some kind of religious order. Perhaps this is a retreat of some kind – away from the world’

‘There are no men here’

‘Except you!’ She smiled and patted his knee. He put his feet up next to hers. His socks were ragged and wet from standing in the doorway for just a second.

‘We’re at the end of the world’ she said.

‘What book are you reading, Lotte?’

‘Robinson Crusoe’

Howard laughed. He found it irresistibly funny. It was so apt! They were like Crusoe himself – wandering the beach looking for footprints.

‘You’ve read it before’

‘I know Howard – but it’s perfect for here, no?’

She said no like a question.

While she read he listened to the strange fizzing noise as the peat burned inside the stove.

In the afternoon, there was a little less rain and Howard was drawn to the window again. The light had changed subtly so the clouds over the houses looked less severe. There was a faint illumination so the grass was yellow-green, almost luminous. One of the sisters was coming through the grass with a wheelbarrow again. Her big coat billowed in the wind and her scarf was almost being pulled from her head. It was still windy even if the rain was dying down.

Howard opened the door and the woman wheeled the barrow right in, her face red with the effort, grey hair streaked across her face. She smiled though. She almost looked apologetic, as if she was sorry for the terrible weather. They helped to unload the peat. They’d almost used up the amount they’d been given the night before. The sisters were very generous.

Mrs Van Dijk thanked the woman and was told via various signs that her name was Brigitte. Before she went out she pulled from her jacket a roll of parchment. It was yellow with age and damp at the ends from rain. She gave it to Mrs Van Dijk signing that Karen had told her to give it to them – to read.

And then Brigitte was gone, wheeling the wheelbarrow along the grassy path. Howard watched her go. The light had changed again, and the grass no longer glowed. The clouds were black over the houses. Rain started to fall again: the weather was closing in for the night.

Mrs Van Dijk unrolled the parchment and sat back on the stool placing her un-booted feet up on the warm iron of the stove. She found it quite comfortable.

‘Ah – the writing’s in English. Something about a saint, a catholic saint’

********************************

She read:

Amma Syncletica of Alexandria, a 4th century Christian saint of the desert, was from a wealthy background. From childhood she was drawn to God and the desire to dedicate her life to him. She gave all that had been bequeathed to her by her parents to the poor. Syncletica abandoned the life of the city and went to live in a desert cave becoming a hermit, gazing out onto the sand each day – at the limit of the world. She gained the attention of local people and gradually many women came to live with her as followers of Christ.

Syncletica cut her hair to renounce the world. Her solitude and humility made a deep impression on her female followers.

St. Syncletica said: ‘how happy we could be, if we took as much time to please God, as we do to gain material things! We work and trade among thieves and robbers and at sea we expose ourselves to the fury of winds and storms, to shipwrecks, to perils to gain worldly wealth’

‘We must be continually on our guard, for we are engaged in a perpetual war; unless we take care, the devil will surprise us, when we are least aware of him. A ship sometimes passes safe through hurricanes and tempests, but if the captain, is not careful a single wave, raised by a sudden gust, may sink the ship. In this life we sail in an unknown sea. We meet with rocks and sands; sometimes we are becalmed, and at other times we find ourselves tossed and thrown by a storm. Thus we are never secure, never out of danger; and, if we fall asleep, we are sure to perish. We have a most intelligent and experienced captain in the form of Jesus Christ himself, who will conduct us safe into the port of salvation’

‘A treasure is secure so long as it remains concealed; but when it is disclosed, and laid open to a bold invader, it is presently destroyed; so virtue is safe so long as it is a secret, but, if exposed, it evaporates into smoke. If you are humble, and have contempt for the world, your soul, like an eagle, soars high, above all transitory things’

‘It’s beautiful’ said Mrs Van Dijk. She sighed putting the parchment the floor beside her. She stretched her legs up.

‘What does it mean?’

‘The sisters must be followers of this St. Syncletica. I’ve heard of the idea of renunciation of the world and of living a pure life’

They listened to the hiss of the burning peat.

‘We’re at the edge of the world’ she said sleepily.

As if in answer to this, a rush of wind and rain slammed into the front of the house. They felt a wave of cool air move in the room. Howard thought he smelled the sea on the rain and even tasted salt on his tongue. He imagined the violent wind far out at sea, scooping the spray from distant waves in deep water, then sweeping up the beach to throw the sea at the little hut. On a night like this it was easy to imagine that the hut was a boat far out to sea, out of sight of land.

********************************

They lay in the dark, listening to the wind. The rain had stopped and there were just rushes of air coming up the beach. They could hear fragments of singing broken by the wind. The sisters were worshipping again.

‘I feel guilty’ said Howard

‘Why?’

‘Because we’re eating their food and using their peat. They must be poor’

‘You can go and cut peat for them’

‘I will – if the weather is good tomorrow’

‘Besides Howard, some of these women might have money. Perhaps they didn’t renounce their wealth’

‘I think they did. They eat everything they grow. They’re self-sufficient. They’ve no need of money’